MY WEATHER FORECASTING

VS. THE WORLD’S

|

MARKETS OF KALSHI

|

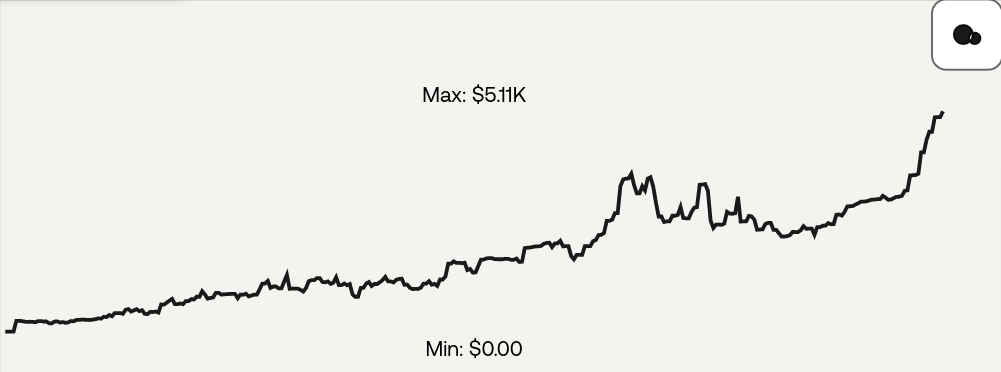

The Growth Curve of Learning a New Location

|

|

|

BACKGROUNDBachelor’s of Science – Meteorology – Texas A&M 2012 Trained by Senior Meteorologist Michael Fagin Since 2014 Trained by Senior Meteorologist Erik Moldstad Since 2022 Have Worked on Projects with Certified Consulting Meteorologist Michael R. Witiw, PhD 2019 Research: Relating F4 and F5 Tornadoes in the United States with Solar Electromagnetic and Geomagnetic Data |

|

|

RAIN

FORECASTS

SNOW

FORECASTS

CUSTOM

FORECASTS

C O N T A C T

RAIN AND SNOW FORECASTING

All forecasts are subject to dramatic changes without much warning. Some types of forecasts, however, are more reliable than others. Winds and atmospheric pressure are the easiest parameters to forecast because the chance of them dramatically changing quickly is smaller than the others. Automated precipitation forecasting has bottom-ranking efficiency: models are due to fluctuate widely by both amounts and timing.

The precipitation process is highly dependent on other atmospheric forces. Concomitantly, precipitation forecasts are highly subject to the errors in the forecasts for other atmospheric parameters. With the exception of systems already organized over vast distances, precipitation processes including cloud formation occur on a scale smaller than a 4-km grid. Even in 2021, the only shot at getting the forecast very close to correct is to tie together a myriad of little guesses and assumptions to substitute perfect real-time data coverage – the post-processing phase, as it’s called in the weather industry. Watching the long-term behavior of individual forecast models provides practical insight into their inadequacies, which builds a meteorologist’s instincts regarding model trustworthiness.

Some precipitation forecasting difficulties are characteristic to specific locations. Terrain, for instance, reshapes and redirects the approach of incoming weather systems. Many locations aren’t distinctly calculated in a 36-km grid spacing, which provides the longest-term forecasts available. Not until about a week before a storm event do the first and most statistically inaccurate 12-km grid spacing models publish, allowing for deeper insight into a potential storm’s approach. 12-km spacing is, however, still a rough estimate, allowing for persistent miscalculations pertaining to the location, timing and precipitation totals of weather events. 4-km models begin to detect weather anomalies such as Puget Sound Convergence Zone events and well resolve the Cascades and Olympics but still cannot well negotiate many smaller obstructions and weather features. Models with closer grid spacing have long been in development but are still little more than experimental and use shortcuts due to computing resource scarcity, leaving much room for error until some day in the distant future when they may be perfected.

Computer models run from incapable to largely incapable when it comes to adequately considering the effects of the interactions of ice, surface friction, water, varying local terrain, varying altitudes, etc. with the atmosphere.

The raw components of weather formation occur on a scale much smaller. Even large eddies, composed of millions of eventually assembled smaller eddies, are only about 1 km2 wide. Well beyond the capacities of current models is inertial subrange turbulence: shear turbulence from eddies of differing sizes interacting. Forecasting large thermals is presently limited to around a half hour out. Forecasting turbulence requires an infinite set of equations and variables, which are reduced in generalized applications to first and second order equations, to model its net influence. Until forecast models accommodate small-scale meteorology as well as large-scale, even the best models will have considerable room for error.

MAXIMIZING EQUIPMENT DEPLOYMENT EFFICIENCY

During significant rain events, stormwater treatment facilities deploy expensive equipment for testing and often must fly in engineers to ensure everything operates properly. Improperly forecasting sufficient stormwater wastes equipment because it can’t be redeployed.

An efficient way to hedge bets against possible losses from misdiagnosing how much it’s going to rain or snow is to hire a professional meteorologist to better determine when resources should be deployed and crew should be alerted. An experienced forecaster can better hone in on when some models may be less accurate than others.

I recently worked for the engineers at NEORSD, who needed to better anticipate precipitation events above 0.25″ in order to decide when to conduct water tests and properly staff the facility. The expenditures related to properly preparing made a seasoned meteorologist’s extra opinion a lucrative addition, despite the cost of hiring me.

Stormwater testing is attempted during events projected to endure well over half an inch of rain within roughly twenty-four hours. Tests may fail due to both insufficient stormwater and an incorrect deployment time range.

While forecasting, I consult the GFS, NAM, ECMWF, UKMO, HRRR, RAP, ICON, ARPEGE, ACCESS-G, GEM and other weather models consistently. Like getting better over time using a set of physical tools, long-term, consistent exposure to the models opens the door for meteorologists to start anticipating outlier figures and judge the real-time performance efficacy of models.

A seasoned meteorologist much more often than naught creates superior forecasts to those offered by automated systems. Some meteorological firms make facilities pay for their services just to relegate the work to their own, self-tested, self-approved, automated systems. At Precipitation Forecasting, the ship is always manned.

The Need for Custom Snow and Ice Forecasting – Case Example: the Schools of Western Washington

Every year, inclement weather brings hazardous road conditions from snow, freezing rain and black ice.

WINTER FORECASTING FOR WESTERN WASHINGTON

Schools in the Greater Puget Sound area begin to worry about winter weather about a month into fall. At low elevations, snow is normally limited from mid-November to early-March. Even during the winter, most precipitation in the area falls as rain. Lowland precipitation west of the Cascades starts at 40°F, so the majority often precipitates before approaching snow formation. It requires a kick of cold air, which is typically well blocked by the Cascades and Rockies.

Certain weather situations, such as a zone of low atmospheric surface pressure, can draw cold air from the Canadian interior southwest through the Fraser River valley. The funneled air bursts out of the west Cascades in what can be sudden, strong northeasterly winds, nearly focused on Bellingham, WA. As the air spills out, temperature forecasts around the Sound often drop quickly and the depth of the critical change is sometimes missed by models. Cold air also may push into the Greater Seattle area from eastern Washington through Snoqualmie Pass if easterly winds are strong enough.

Certain weather situations, such as a zone of low atmospheric surface pressure, can draw cold air from the Canadian interior southwest through the Fraser River valley. The funneled air bursts out of the west Cascades in what can be sudden, strong northeasterly winds, nearly focused on Bellingham, WA. As the air spills out, temperature forecasts around the Sound often drop quickly and the depth of the critical change is sometimes missed by models. Cold air also may push into the Greater Seattle area from eastern Washington through Snoqualmie Pass if easterly winds are strong enough.

Some western Washington forecasts struggle for easily understandable reasons, given the most quality forecasts have a grid spacing of 4-km. Most hills, for instance, possess microclimates of their own, based on windward directions, solar angles, vegetative and soil differences, etc. Infrequently measured data over the Pacific limits potential warning of incoming systems and the count of model updates before a storm hits. Many forecast areas are commonly in precipitation shadows, often leading to excessive forecast totals or unstable forecasts, where a school district prognostically hops in and out of a shadow. Snow cover is far more often than naught quite non-uniform between the mountain ranges, with hills often having a snowy side and a more radiation-absorbent bare ground side. Models that are largely wrong about existent snow cover can make a multiple degree forecast error.

Essential to forecasting winter weather, local temperature contrasts have important regional characteristics. More typically than naught, western Washington has small but noteworthy nighttime local temperature variations. The bottom of a hill just a few hundred feet high is often 2-7°F cooler than its top. Cooling sea breezes and warming land breezes are very frequent and function without requiring an incoming atmospheric disturbance.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) adds character to local snowfall patterns. Recent La Niña years have typically dropped as much as three times the regional snowfall seen during El Niño years. Paradoxically, regional record snowfall years tend to be ENSO near-neutral years: those with a very typical equatorial Pacific Ocean temperature distribution. A one degree difference in the 850 mb atmospheric level’s temperature – a pivot around -8°C – can differentiate rainfall and snowfall. Southerly or southwesterly flow often feeds moisture to the area but is often too warm for snow. Northerly winds often bring the cold needed to turn rain to snow but tend to be drier, which enhances evaporation, limiting ground-reaching precipitation. Snow and ice on the ground may be enough to shift potential rainfall into snowfall but may not be adequately noticed by models: online webcams can add necessary detail. Relative to the neighboring terrain, each locality responds differently to the region’s characteristic wind patterns. Terrain with variations unnoticeable on 12-km or 4-km grid resolution is more error-prone.

Melting and evaporation can cool air that’s in the mid-30°F enough to change rain into snow or a wintry mix. Heavier precipitation yields increased melting and evaporation, which further cools the air. Prolonged regional cold air, especially after winter has already taken over the landscape, can transition rain from an encroaching Low into snow.

School snow forecasting using the aforementioned forecasting tips by molding them to a specific district can yield better weather judgments. Doing so, however, would require meteorologically confident staff monitoring the weather all winter, all day and all night. Another complication is that models aren’t everything: some of the knowledge and insight that steers a professional meteorologist’s decisions may not even come from computer-generated clues.

West of Oklahoma City, southeastern Washington sees the most freezing rain: 10-20 annual hours. Sometimes that weather can extend west, namely through the Columbia Gorge. In that and other weather scenarios, icy conditions may manifest locally. frozen street Freezing rain is very dangerous when it does form but is tricky to predict. A delicate balance of temperatures aloft must be maintained in order for precipitation to not fall as snow, mixed precipitation or warm (> 32°F) rain. The delicate balance can be strengthened by cold valley air if warm, moist, mountain air also exists. Temperature-changing flows, such as through river valleys and breaks in mountain ranges, need to be closely monitored and accounted for in a winterly western Washington forecast.

Mixed precipitation, much more common than freezing rain, also poses a big regional traffic risk. If it’s a big, sloppy mess, it better not all freeze the next morning or while school is in session.

Dense fog under high pressure is common in western Washington and, far more often than freezing rain, produces black ice. Intersections, bridges, windswept sections of roads and other areas of notable automobile heating and subsequent cooling are particularly vulnerable to its formation. Black ice may also form from incoming cold air freezing both freshly fallen rain and thawed snowmelt.

Beyond safety, turning to a seasoned meteorologist for help with school closing decisions can save time, public funds and headaches.